The Journey |

From Stonington to Petersburgh...a Journey of Migration and Resettlement.

by

Daniel J. Bornt

by

Daniel J. Bornt

Two British sailors who had been pressed into service jumped ship

along the New England coast in the 1660's and lived with the Indians

for a time to avoid being caught. The two sailors, Church and Stewart,

formed a bond of friendship and swore the two families would always

be closely associated. - Family legend according to Frank Church

| ...It would seem that the wheelwright of the pioneer era put a major part of his effort into two-wheeled carts rather than the conventional four-wheeled wagon. There are at least two good reasons for this. One was the greater simplicity of cart construction. Possibly the dominant reason however for the prevalence of carts was that the fields where the harvest must be gathered were still studded with stumps and sprinkled with boulders. A cart was easier to get around such obstructions than a four-wheeled vehicle. There was only one pair of wheels to watch. The heavy two-wheeled cart was once almost universal. The diameter of the wheels of the early vehicles was notably greater than on similar wagons nowadays. Big wheels have high clearance which enable the driver to straddle a low stump or boulder. A high wheel rolls better over muddy or rough road.*(1) |

In 1780 or thereabouts, John Church at 49 years old, his wife Hannah and their four children, John, 23, Nathaniel, 21, Hannah, 17, and Elizabeth, 15, along with 51-year-old Eliphalet Stewart and his clan - his wife Elizabeth (Church?) and some or all of his seven children - arrived in the Van Rensselaer Manor "Rensselaerwyck" in eastern New York State. Here they would begin their lives anew as leaseholders in the manor's unsettled hill sections overlooking the valley of the Little Hoosac. They were not alone in this endeavor. Many of their eventual neighbors in the mountainous adjoining districts in the East Manor would be recent immigrants from the New England/Connecticut Valley colonies.

The reasons why the Churches and Stewarts left Stonington, Connecticut, and the seacoast of New England, where the Church family's ancestoral beginnings were a part of the Puritan foundings of Plimoth Plantation and the Massachusetts Bay Colony, are now obscure from this vantage point of two hundred-plus years since our colonial era. A few tantalizing clues remain - see our Genealogy and the Church History in Petersburgh. Whatever their immediate impetus, they were in the vanguard of the continual, restless migration towards the west that has characterized the American spirit - the crossing of the intimidating width of the Atlantic from our European mother countries, our first lonely steps upon the shores of this bountiful continent, and then the relentless march toward the setting sun.

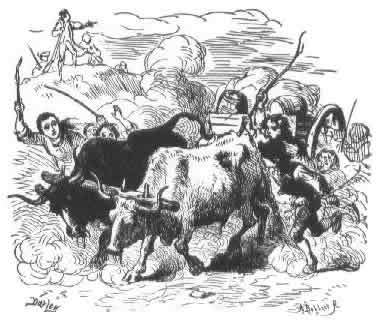

We can only speculate as to their mode of travel, what they carried with them, and what they needed to bring for a pioneer's homestead in a rugged, sparsely-settled region. Maybe they had a version of a “Conestoga” wagon pulled by stout slow-moving oxen with a cow and a couple packhorses tethered behind. Perhaps they left Stonington virtually penniless and unable to even afford a wagon, the men walking with the womenfolk riding sidesaddle on horses, and all their worldly possessions bulging out through canvas bundles tied on the backs of overburdened horses and mules.

What might be some of the necessary implements and household items that a family might need to survive in an area where Indians had not too many years previous freely roamed, and where the trappings of civilization were still sparse and uncertain at best? Surely they had to have important iron and wooden tools for clearing, planting, and building: axes and adzes and shovels and hoes, and a plow of some sort; kettles, ovens, barrels and buckets for cooking and washing and storing water; spoons, knives, awls, needles, pins, fishing hooks, and all the other miscellaneous items for a self-sufficient farm life.

This list could go on and on, and probably would include clothes and bedding, physics, medicines, the family Bible, and important papers; and then, until the lands were cleared and the crops planted and harvested, a family must have some consumables to survive: flour and meal, grease and lard, and powder, flint and lead for the muskets to bring down game and protect one and one's livestock from bears and lions and wolves. It seems like just the bare necessities would have filled a couple wagons all by themselves.

In Carlton Church's History of the Church Family of Petersburgh, NY, he speculates that the Churches didn't move to their new Rensselaerwyck farm leases immediately, but perhaps made several trips back and forth from Stonington to ready the place for the womenfolk. (We know that Lemuel Stewart in 1782 returned from Little Hoosac to Preston, Conn. where he married Rebecca Rose.) We would venture a guess that our stalwart ancestors had at the minimum a two-wheeled cart pulled by a single-yoke of oxen* (1), at least for the final move to bring the women and all their household goods.

The

roads upon which this journey embarked were a far cry from the sleek smooth

hardtopped highways which we of today are accustomed. In an American history

book of the early 20th century we read:

The

roads upon which this journey embarked were a far cry from the sleek smooth

hardtopped highways which we of today are accustomed. In an American history

book of the early 20th century we read:

“In nothing has there been a greater change in the last hundred years than in the means of travel. For two thousand years, as Henry Adams says, to the opening of the nineteenth century, the world had made no improvement in the methods of traveling. That century brought the river steamer, the ocean greyhound, the lightning express train, the bicycle, the electric car, and the automobile.

In colonial times travel by land was in the old-fashioned stagecoach, on horseback, or afoot. The roads were usually execrable. Many of the towns were wholly without roads, being connected with their neighbors by Indian trails. The best roads to be found were in Pennsylvania, all centering into Philadelphia, and on these at all seasons the great Conestoga wagons lumbered into the busy city, laden with grain and produce from the river valleys and the mountain slopes. Long journeys were often made on foot by all classes. A governor of Massachusetts relates that he made extensive journeys afoot, and speaks of being borne across the swamps on the back of an Indian guide. A favorite mode of travel was on horseback. A farmer went to church astride a horse, with his wife sitting behind him on a cushion called a pillion; while the young people walked, stopping to change their shoes before reaching the meetinghouse. Great quantities of grain and other farm products were brought from the remote settlements on pack horses, winding their weary way through the lonely forest by the Indian trails.

Coaches and chaises were few until late in the seventeenth century. Not until 1766 was there a regular line of stagecoaches between New York and Philadelphia. The journey was then made in three days; but ten years later a new stage, called the “flying machine,” was started, and it made the trip in two days. A stage journey from one part of the country to another was as comfortless as could well be imagined.”

Source:

History of the United States of America, by Henry William Elson, The MacMillan

Company, New York, 1904. Chapter X p. 208-210

Transcribed by Kathy Leigh

The previous account paints a fairly grim picture of travel in colonial days. But by the last decades of the eighteenth century as new settlements sprang up and the old ones grew, the roads expanded through the forests and the countryside to connect the various settlements, replacing the narrow Indian trails and horsepaths. The necessities of trade and communication couldn't help but make it so. Certainly these tracks weren't gravelled or smoothed like we would expect a dirt road today to be, but during dry summer weather the hard, rocky ground of the region wouldn't unnecessarily impede travel by horse or cart either.

In “War over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement on the Bennington Battlefield - 1777,” Philip Lord writes:

“In quality, the roads of the eighteenth century in rural areas would be less similar to our unpaved country lanes (intended for auto travel) than to our farm field paths (intended for infrequent use by tractors and farm machinery). Such roads today are little more than tracks, worn into the native soil, with a few rocks or logs thrown into the ruts and mudholes that use in wet seasons inevitably produces. In this they approximate the normal conditions of the common eighteenth century highway.”* (2)

Many of our highways today generally trace the original roads that existed in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York in the few years after the Revolution. Some of those early travel-ways were abandoned as new villages sprang up off those original routes and gained importance as places in which to go, or when newer roads created “shortcuts” that rendered the older roads obsolete. In viewing our 1780 map of Connecticut we can see that the various towns were even then connected by a substantial road network, one which is extensively overlayed today with Connecticut's present highway system.

The most direct route that we can discern from Stonington to the northwest toward the Little Hoosac area would take us through the Connecticut towns of Groton, New London, East Haddam, Haddam, Middletown, New Cambridge, Litchfield, and Cornwall up to Sheffield, Massachusetts. Of course, in 1780 local roads weren't numbered and hardly even named, obviously highway maps weren't available at filling stations, and published maps of any kind were of such scarcity they were probably only in the hands of the wealthy or the military. So one would had to have had much familiarity of the countryside to realize that this route we are suggesting was indeed the most direct, so it is possible that the Churches and Stewarts may had another more familiar and favorite path that they followed being much longer but more advantageous than the one we are looking at.

However, since John Church's fellow immigrant Eliphalet Stewart and his two sons Eliphalet and Lemuel all served in various Revolutionary militias it could be that they had covered much of the area during their military service and were well acquainted with the roads that would take the family to the Little Hoosac hills.

Due to the terrible conditions of mud and bog that afflicted the roads during the spring and fall, we must assume that this journey wasn't commenced until April or May. “Usually serious travel, especially with heavily loaded vehicles, was reserved for the summer months. In due time after the roads were settled, the teams were sent back for the cart, wagons, and furniture...” - Levi Beardsley, Hoosick 1789, (in describing his own family's move.)*(3)

By the highways of today following the route mentioned above, the distance from Stonington to Sheffield is approximately 120 miles. Considering the speed of an ox-drawn cart [“The average 2-oxen cart can pull 1,000 to 1200 lb. at 2 mph.” (Engels 1978:15)] at no more than ten to fifteen miles per day, if that, it took the families about a week and a half to traverse Connecticut through an area that was relatively settled, and where the roads would apt to be somewhat better traveled and more accessable through greater use.

Continuing northward from Sheffield, we can see on the 1780 map of eastern New York they could pick up main road to Albany around Stockbridge to cross the Berkshires over into New York. From New Lebanon, NY they could have then traveled due north up along the Little Hoosac Creek to the township eventually created in 1791 as Petersburgh, but at that time ten years earlier known as a Manor district bearing the same name as this creek that flowed through it.

As they journeyed northward the settlements spread out and the springtime that had arrived in southern Connecticut became chillier. The frost of the previous winter could still have been working out of the ground on the less traveled roads and could have slowed down the plodding progress of the oxen further. From Sheffield to Petersburgh the distance along present roadways is about 60 miles. With our oxcart slowed down to six miles a day over rougher, hillier terrain and worse road conditions, we add another ten days to our journey.

In conclusion, the Churches and Stewarts must have been on the road about three weeks to a month until they reached their new homelands in late May or early June in the Little Hoosac District in Rensselaerwyck.

Our 1780 maps of the eastern NY and western Vermont and Massachusetts regions show the boundaries of the Van Rensselaer's vast manor, and the steep mountain ridges on either side of the Little Hoosac's northward course. Along the main Hoosac River's gap through the eastern ridge at Pownal we can see the Deerfield - Albany road from Fort Massachusetts at Williamstown, established in 1753. “Mount Belcher,” the prominence at the height of Petersburgh Pass as it was christened by the mapmaker at that time, lies directly opposite the ridge on the western side of the Little Hoosac valley where the Churches claimed their homestead.

Now the backbreaking labor of carving a home out of the wilderness begins.

Next: The Homestead

Notes:

For most of the pages in this web site we have cited the "Hoosic" river and its tributaries. However, on this page, in keeping with the spelling syntax of "Hoosac" as shown on the referenced maps, we have spelled it as "Hoosac." - Ed.

*References:

(1)

"War over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement on the Bennington

Battlefield - 1777" by Philip Lord, New York State Museum Bulletin

No. 473 ISBN 1-55557-186-7 "Transportation," p121

(2) Ibid. "Conditions," p27

(3) Ibid. "Conditions," p29

- Article revised by Daniel J. Bornt 6/4/2003

Church Home || Genealogy || Frank and Myrtle || History of Church Family in Petersburgh || Background of Settlement || The Homestead

"The

Church Family of Petersburgh, NY featuring descendants of Frank and Myrtle

Church" website

at http://churchtree.tripod.com

©2002 by Daniel J. Bornt,

e-mail to: vanatalan@yahoo.com